“We recognize that statelessness can be a root cause of forced displacement and that forced displacement, in turn, can lead to statelessness.”

New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2016

KEY MESSAGES

- Statelessness and migration, including forced migration – involuntary displacement – have a strong interaction: statelessness can cause (forced) migration and (forced) migration can cause statelessness.

- Children of refugees and migrants can be at risk of statelessness, for instance when there are limits to the conferral of nationality by a parent if the child is born abroad, or barriers to accessing birth registration in the host country.

- Being stateless can create additional vulnerabilities for refugees and migrants, especially if their statelessness is not identified or recognised and the response to their situation is not tailored accordingly. Statelessness can increase the risk of human trafficking and immigration detention.

- The international law frameworks for the protection of refugees and stateless people have a shared history and take a similar approach, although the refugee convention has been more widely ratified and offers slightly stronger protection on some issues.

- Not all refugees are stateless, and not all stateless people are refugees. Where a person is both stateless and a refugee, it is important that both types of status are explicitly recognised.

STATELESSNESS AS A CAUSE OF (FORCED) MIGRATION

Many of the largest stateless communities globally are subject to racial, ethnic, and religious discrimination. Exclusion from nationality as well as stripping people’s nationality leaves individuals and communities in vulnerable circumstances, unable to exercise any rights or enjoy protection. This means that stateless people often find themselves in highly precarious and vulnerable situations in their countries of origin or where they habitually reside: their statelessness is one element of the detrimental treatment they endure, often characterised by a wide range of other human rights violations.

The level and extent of the human rights challenges faced by stateless people differs between countries and between different stateless groups and individuals. The discrimination faced by stateless people can be so severe that it amounts to persecution, and can put them at the centre of local tensions or internal conflict, forcing them to flee their homes or to cross international borders. Statelessness can therefore be a driver of migration and stateless populations are uniquely vulnerable to and at risk of forced displacement in the context of conflict, serious human rights abuses, collective expulsions and even natural resource management, for instance due to lack of land rights.

In situations where a stateless person is forced to flee their country to seek asylum abroad, the fact that they have no nationality can make the pursuit of international protection more challenging. Without a travel document – or perhaps even any identity document at all – stateless people may be forced to use illicit means to cross international borders, making them more vulnerable to human trafficking. Upon arrival, it may be more difficult to access international protection and assistance, because a stateless person might not be able to ‘show’ where they are from and this may affect the outcome of their asylum claim. Statelessness can also obstruct access to naturalisation, family reunification and resettlement programmes, making durable solutions harder to achieve. Statelessness determination procedures are key to ensuring the adequate identification and protection of stateless people in the context of (forced) migration.

STATELESSNESS AS A CONSEQUENCE OF (FORCED) MIGRATION

There are a number of reasons why people may become stateless or be at risk of statelessness after migrating or being displaced from their country of origin. Documents can get lost or destroyed during a conflict that has forced people to flee their country. Being undocumented is not synonymous to statelessness but it heightens the risk of a person becoming stateless. In countries where documentation systems are not digitised, it becomes difficult to re-acquire ID documents or find proof of nationality if documents are lost. Major political changes in the country of origin can also affect migrants and refugees who are outside the country when this happens. For instance, state secession and re-determining who belongs to the new state can exclude those who have migrated or are displaced, increasing the risk of becoming stateless.

Some displaced communities have lived abroad for decades, with more than one generation born in exile abroad. The nationality laws of some countries prescribe loss of nationality on the basis of a certain period of residence abroad, when prolonged absence from the country is viewed as eroding the genuine bond with the country, or switching allegiance to another country. Statelessness can arise if a person in such circumstances has not acquired another nationality, for instance due to barriers to naturalisation in their country of residence. The nationality law of the country of origin may also limit the conferral of nationality by its citizens for children born abroad, which could leave children born to migrants or refugees at risk of statelessness. Even if the law allows for access to nationality by descent for a child born abroad, it can be difficult to establish nationality in cases where the child is unable to access birth registration in the host state – for instance because the procedures are complex or inaccessible for migrant or refugee parents.

INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORKS FOR REFUGEES AND STATELESS PEOPLE

International refugee law and international statelessness law share common roots. After World War II, the UN commissioned a “Study of Statelessness”, to determine how to deal with the situation of the millions of people who were left displaced and denationalised (both refugees and stateless people). This laid the foundations for the development of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons (followed later by the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness). Respectively, these instruments provide the international law definition of a refugee and a stateless person; setting out a minimum set of rights to be guaranteed to individuals who qualify under the definition.

The rights set out in the two conventions are very similar, although the 1951 refugee convention offers stronger protection in some areas than the 1954 statelessness convention, including in relation to the prohibition of refoulement (forcible return) and protection against penalties for illegal entry. As such, “protection under the 1951 Convention generally gives rise to a greater set of rights at the national level than that under the 1954 Convention”. To date, the 1954 statelessness convention has also not attracted the same level of ratification as the 1951 refugee convention or other human rights treaties. As a result, there is more limited state practice on the application of the 1954 statelessness convention than the 1951 refugee convention, including jurisprudence of national courts. There has also been less academic writing about the international protection system for stateless people.

STATELESS VS. REFUGEE

A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. They may still hold the nationality of their home country – in fact, the majority of refugees have a nationality – but international law specifies that they should be given protection because it is unsafe for them to return home. A stateless person is someone who is not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law. They may be residing in the country of their birth and ancestry, and in fact, most stateless people have never crossed an international border. They must be provided with protection, as specified by international law, due to the absence of the legal bond of nationality, and the rights and protections associated with it. It is also possible for a person to be a stateless refugee: if they meet the definitions under the 1951 refugee and 1954 statelessness conventions, they qualify for protection under both.

According to the UNHCR Handbook on the Protection of Stateless Persons, if a person raises both a refugee and a statelessness claim, “it is important that each claim is assessed and that both types of status are explicitly recognised”. Identifying whether a refugee is also stateless is important in the context of preventing the perpetuation of statelessness, for instance by triggering safeguards for a child born to a stateless refugee to ensure that their right to nationality is realised. There may be instances “where refugee status ceases without the person having acquired a nationality, necessitating then international protection as a stateless person”.

[Last updated: October 2023]

Cover image by Greg Constantine

Further reading

Voices & Experiences

-

Insecurity and exploitation for Rohingya in Bangladesh’s refugee Camps

![Bangladesh]()

Insecurity and exploitation for Rohingya in Bangladesh’s refugee Camps

![Bangladesh]()

“What the Rohingya community is facing in terms of trafficking, detention and exploitation is linked to the statelessness that has been forced on them. The dangerous sea and land journeys Rohingyas are compelled to or forced to take are just because the Rohingyas don’t have travel documents. And they don’t have livelihood opportunities in Myanmar or Bangladesh. They also don’t have development opportunities including education or life skills development in refugee camps in Bangladesh or Myanmar. For example, many women who are being trafficked to Malaysia go there just to get married. If they had a travel document from Myanmar, they wouldn’t have to take risky journeys. They are forced to. That’s where the exploitation begins.”

Rohingya Human Rights Defender

The Rohingya community was arbitrarily stripped of citizenship in Myanmar in the 1980s. Violent persecution and acts of genocide have forced large numbers to flee their home country and seek safety abroad. According to official statistics, Bangladesh hosts almost a million Rohingya refugees. However, Rohingyas are treated in Bangladesh as irregular migrants instead of being recognised and protected as stateless refugees. The lack of access to legal status or the right to work, and with children and youth prevented from accessing formal education and training, has driven men and women into precarious work in the informal sectors of the economy with few safety standards, often exposed to exploitation and with no access to social safety nets.

-

Migrants and their descendants face barriers accessing dual nationality in Zimbabwe

![Zimbabwe]()

Migrants and their descendants face barriers accessing dual nationality in Zimbabwe

![Zimbabwe]()

“Denying us identity documents as migrants does not only affect adults’ rights but denies our children their rights. It is not only destroying parents but the next generation.”

Affected Person

Zimbabwe has a long history of immigration from Southern African Development Community (SADC) neighbouring countries such as Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia. These migrants and their descendants have been repeatedly subjected to arbitrary denial or deprivation of Zimbabwean nationality due to their foreign origin. While migrants were initially allowed to retain their original nationality and acquire Zimbabwean citizenship as dual citizens, the 1984 Citizenship Act introduced a requirement for those with dual nationality to renounce any foreign citizenship in order to retain their Zimbabwean citizenship. Despite changes to these rules in Zimbabwe’s 2013 Constitution, many who attempt to register as Zimbabwean or obtain nationality document are often still directed to renounce citizenship of their parents or grandparents’ country of origin, which may be impossible in practice.

Voice from We Are Like “Stray Animals” Thousands Living On The Margins Due To Statelessness In Zimbabwe

-

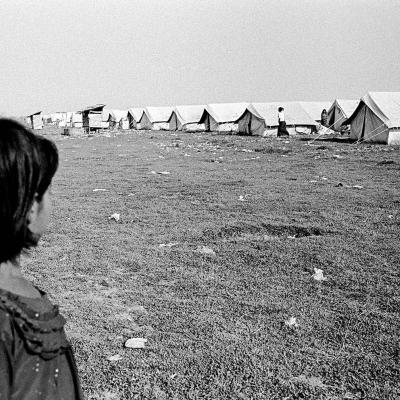

Stateless Palestinians in Syria

![Syria 1]()

Stateless Palestinians in Syria

![Syria 1]()

“The first thing they wrote when I told them that I am Palestinian-Syrian... They registered me as statslös, stateless, like I have no country that I belong to, that I have no nationality. So, I was stateless, and this is something that makes you wonder: If I’m stateless and I’m considered stateless, where do I come from? What are my origins? Who gave me the right to be Palestinian?”

Zahra

Affected person

As a consequence of the deteriorating situation in Syria, between 2011 and 2017 over 120,000 Palestinian Refugees from Syria sought refuge in other states. Of those Palestinian refugees who remain in Syria, the vast majority have been internally displaced. For those who crossed an international border, a process of re/de-labelling began.

Voice from https://statelessnessandcitizenshipreview.com/index.php/journal/article/view/275/193

Latest Resources: Refugees and migrants

-

Rethinking the Concept of a “Durable Solution”: Sahrawi Refugee Camps Four Decades On

Type of Resource: Academic publication

Theme: General / Other

Region: Middle East and North Africa

View -

Forced Population Transfer: Segregation, Fragmentation and Isolation

Type of Resource: Other

Theme: (Forced) Migration

Region: Middle East and North Africa

View -

Denial of Palestinian Use and Access to Land Summary of Israeli Law and Policies

Type of Resource: Other

Theme: (Forced) Migration

Region: Middle East and North Africa

View