“Stateless minorities are often doubly vulnerable. The discriminatory denial or removal of citizenship may have long-lasting and extreme consequences for the enjoyment of other rights.”

Fernand de Varennes, former UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues

KEY MESSAGES

- Discrimination against minorities is a major driver of statelessness: it can cause statelessness, put groups at risk of statelessness, and maintain intergenerational statelessness.

- More than 75% of the world’s stateless population belong to minority groups.

- Statelessness intersects with and exacerbates barriers that minority groups already face, resulting in a restriction of access to basic rights and services, and leading to further discrimination, both by the state and non-state actors.

- Minorities are made stateless or at risk of statelessness for a variety of reasons, and the majority of the causes of statelessness affect minority groups. These include historical (forced) migration, state succession, mass deprivation of nationality, and discrimination.

- Various international conventions protect minorities and indigenous peoples’ right to nationality, without discrimination, and minority statelessness is gaining increasing attention in international human rights mechanisms such as the UPR.

- Increased mobilisation in recent years by minority groups themselves has led to successful strategic litigation, paralegal work, and advocacy.

MINORITIES AND STATELESSNESS

It is estimated that more than 75% of the world’s stateless population belong to minority groups. Minority groups are disadvantaged ethnic, national, religious, linguistic or cultural groups, with a distinct identity, who number fewer than the rest of the population of a country. Discrimination against minorities is a major driver of statelessness: it can cause statelessness, put groups at risk of statelessness, and maintain intergenerational statelessness.

Minorities are often discriminated against on a variety of grounds – including, but not limited to race, minority status, religion, ethnicity, belief, language, gender, sex, disability, as well as multiple forms of discrimination (which is known as intersectional discrimination). Access to nationality may be denied on the basis of one or more of these grounds, for instance if the law lists specific ethnic groups who qualify for citizenship or sets religious criteria for naturalisation. Explicit legal “disqualifiers” are relatively rare, but it is more common for laws that appear neutral to be applied in a way that discriminates against minority groups in practice – for example by setting unreasonable administrative requirements to confirm citizenship.

Multiple discrimination can also affect the nationality rights of minority groups. For instance, women belonging to minorities can be further marginalised and stigmatised by gender discrimination in nationality laws, affecting their ability to acquire, change, or retain their nationality, as well as confer nationality to their children. Minorities may also be at increased risk of deprivation of nationality – affecting both entire groups, as well as individuals.

The underlying drivers of discrimination against minorities are numerous, and include racism, xenophobia, discrimination on the basis of ethnicity or nationality, as well as religious or gendered prejudice. Drivers of discrimination often revolve around a state’s desire to shape its polity, based on a particular conception of national identity. Prejudice rooted in ethno-nationalism, where the nation is defined in terms of “assumed blood ties and ethnicity”, results in the exclusion of certain groups, or even scapegoating and blaming of minorities for a state’s failures – economic, political, or otherwise. Minority groups, once stateless or at risk of statelessness, take the brunt of further state discrimination – with other restrictions or forms of exclusion justified because they are not citizens of that country. Statelessness thereby intersects with and exacerbates barriers that minority groups already face, resulting in limited access to basic rights and services, and leading to further discrimination, both by the state and non-state actors.

STATELESS MINORITIES AROUND THE WORLD

Nearly all causes of statelessness affect minority groups in some way. Moreover, there are minority groups affected by statelessness in most countries in the world – some large minority populations, and others much smaller. Many countries even have several minority communities, who all face distinct issues due to lack of nationality, or difficulty proving nationality.

Minority groups can have their nationality arbitrarily deprived by a state. This may happen in a state that they have always lived in, or upon the creation of a new state at independence, or when boundaries and territories are contested. Nationality laws may be (re)formulated based on a particular notion of national identity, with minorities at the fault lines. Examples include the several million Rohingya, an ethno-religious minority from the Rakhine region of Myanmar, who were arbitrarily deprived of their Burmese nationality and the majority of whom have since also been forcibly expelled as a result of severe human rights violations, persecution and genocide. In the Dominican Republic around 130,000 Dominicans of Haitian descent, whose parents or grandparents migrated from Haiti to work on sugar cane plantations, were retroactively stripped of their citizenship in 2013. In India, growing Hindu nationalism has caused minority groups – in particular, Muslim population – to be at greater risk of exclusion, including in the context of the administration of the new National Register of Citizens in Assam, in 2019.

State succession and decolonisation has led to nationality problems for many minority groups, including a large population of ethnic Russians in both Latvia and Estonia, who were left as non-citizens upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1990. Minority groups may have ancestral roots in other countries. Their parents, grandparents or great-grandparents may have migrated from neighbouring countries, either voluntary or forcibly, and have been unable to acquire the nationality of the new country due to restrictive immigration policies, lack of knowledge of registration, loss of documents during travel, or discriminatory laws and policies. Minorities in Kenya are one such example, whereby groups that arrived in the country pre-independence, including the Pare (historically from Northern Tanzania) or the Nubian community (historically from Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan), have struggled to acquire citizenship. Migrants who were brought to Cote D’Ivoire from neighbouring countries to work on tea plantations, and their descendants, are another such group, with hundreds of thousands having difficulty proving or establishing their nationality on the basis of the nationality laws adopted following independence and continuing to struggle with statelessness today.

Indigenous groups, nomadic groups, and travelling groups such as the Roma, are also at risk of statelessness as a result of long-standing discrimination. North Macedonia and Montenegro are among the countries with significant Roma populations, where members of the Roma community face entrenched discrimination and prejudice, including in some cases struggling to access documentation and establish their citizenship. In the sea-borders between Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia, the Bajau Laut, a nomadic, sea-faring community, also experience documentation issues and discrimination. In Thailand, there are approximately half a million people belonging to ethnic minority communities also known as “Hill Tribes” who struggle with civil registration and immigration regulations, which prevents their acquisition of Thai nationality.

PROMOTING THE RIGHT TO NATIONALITY FOR MINORITIES

Various international standards protect the right to nationality for minority groups, including the ICCPR, ICESCR, CERD, CRC, CAT, CEDAW, CMW, and CRPD. CERD Article 5(d)(iii) explicitly prohibits discrimination in the enjoyment of the right to nationality, as well as containing broader principles of non-discrimination and equality. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) also provides in Article 6 for the right to nationality for indigenous peoples, and in Article 2 for non-discrimination.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities also provides important guidance, and the UN forum on Minority Issues plays a key role in promoting dialogue and encouraging adherence to the UN declaration, meeting annually to discuss key thematic issues. In 2018, the 11th session was specifically dedicated to statelessness as a minority issue. The work of the UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues, who is mandated to raise awareness and increase visibility of minority issues, is also key in ensuring minority issues remain on the human rights agenda.

Minority issues have also gained more attention within the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) mechanism of the UN Human Rights Council. In the first cycle of the UPR, just 5 recommendations related to discrimination in the enjoyment of the right to nationality on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, and disability – but this climbed to 28 recommendations during the 3rd cycle. Nevertheless, the attention given to nationality rights represents only a tiny fraction of the total recommendations dedicated to minority rights, racial discrimination or freedom of religion within the UPR. UN Treaty Bodies, including the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) have also been active in certain country contexts in making recommendations in situations of racial, ethnic or religious discrimination in the enjoyment of the right to a nationality.

Further, in recent years there has been increased mobilisation by minority groups to claim their citizenship rights, including through strategic litigation by groups in Bangladesh, Kenya and the Dominican Republic, as well as paralegal work in countries such as Kenya.

[last updated January 2024]

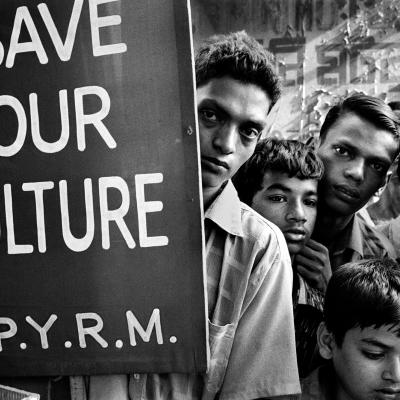

Cover image by Greg Constantine

Voices & Experiences

-

Religious discrimination in India’s Citizenship Amendment Act

![India]()

-

"The Weight of Paper"

![The Weight of Paper]()

"The Weight of Paper"

![The Weight of Paper]()

"The Weight of Paper" United States, 2021. Pencil and ink on paper by artist Mawa Rannahr.

Born in Soviet Central Asia, painter Mawa Rannahr became stateless after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Mawa uses painting to connect her deep emotions and pains with her conviction that no human being should ever be reduced to their nationality status. Her painting entitled “The Weight of Paper” depicts the burdensome administrative processes that most stateless minorities must go through in their daily lives.

-

Restrictions on human rights for Rohingyas in Myanmar

![Myanmar]()

Restrictions on human rights for Rohingyas in Myanmar

![Myanmar]()

“People are facing challenges to access livelihoods and problems with movement restrictions...I do not receive any humanitarian assistance as we are not Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). But we all are facing the same challenges and difficulties like IDPs.”

Affected person

An estimated 600,000 Rohingya remain in Rakhine State, without access to nationality and with severe restrictions placed on their human rights. Of these, 126,000 are effectively confined to camps or camp-like settings that were established in 2012. Without freedom of movement to access decent work and livelihoods, camp residents are dependent on food rations and services provided by aid agencies.

Voice from https://www.institutesi.org/resources/dangerous-journeys-through-myanmar

Latest Resources: Minorities

-

Article: Rohingya Children Grow Up Without Education, Family Life, As India Holds Parents Indefinitely In Detention Centres

Type of Resource: News/ Media reporting / Blog

Theme: Detention

Region: Asia / Pacific

View -

Blogpost: International Law Omissions: Rohingya Deportation Order of the Supreme Court of India

Type of Resource: News/ Media reporting / Blog

Theme: (Forced) Migration

Region: Asia / Pacific

View -

Article: British Citizenship Of Six Million People Could Be Jeopardised By Home Office plans

Type of Resource: News/ Media reporting / Blog

Theme: Nationality Deprivation

Region: Europe

View