“I’m happy to get the documents. It will allow me to go forward in what I want to do … I’m going to fight for others in the same situation as us. I’m going to help them, because I will have the means to do it.”

KEY ISSUES

- Côte d’Ivoire has one of the largest reported stateless populations in the world.

- Statelessness mainly affects the descendants of migrants to Côte d’Ivoire as a result of gaps in the implementation of the nationality law adopted after independence and subsequent amendments to the law in 1972 that restricted access to nationality.

- The nationality law does not provide for access to nationality based on birth in the territory, even for children who would otherwise be stateless or for foundlings – although a circular issued in 2019 does provide for the possibility to issue certificates of nationality to children of unknown parents.

- Access to nationality, identity documents and voting rights were central questions in the civil war in Côte d’Ivoire in the early 2000s.

- Côte d’Ivoire acceded to both UN Statelessness Conventions in 2013 and became the first country in Africa to introduce a statelessness determination procedure in 2020.

- Côte d’Ivoire has made pledges made to ensure a route to nationality for stateless children and to remove remaining gender discrimination from its nationality law, but these have not yet been implemented.

STATELESSNESS IN COTE D’IVOIRE

Côte d’Ivoire has one of the largest recorded stateless populations in the world. At the end of 2023, the stateless population in Côte d’Ivoire was reported by UNHCR to be 930,978. An extensive mapping study conducted in 2018 by UNHCR, the government of Côte D’Ivoire, and the National Institute of Statistics estimated that as many as 1.6 million people in the country were either stateless or at risk of statelessness.

Descendants of pre-independence migrants and members of ethnic groups perceived as migrants - including the traditionally pastoralist Fulani (known as Peul in French), as well as those originating in the northern part of the country - are most likely to be affected by or at risk of statelessness. The French colonial government recruited several hundred thousand people, sometimes by force, from what are now neighbouring countries to work on plantations. Their status and that of their descendants born in Côte d’Ivoire was not clearly established by the Nationality Code adopted in 1961 by the newly independent state, and transitional provisions for facilitated acquisition of nationality were not accessible in practice.

Although the Nationality Code provided for nationality based on birth in Côte d’Ivoire after independence unless both parents were “foreigners”, the lack of clarity of the status of these pre-independence migrants meant that the status of their children was also unclear. The right to acquire nationality by option for a person born in the country, if still resident there at the age of majority, was removed by amendments adopted in 1972 - and in any event, like the transitional provisions, it had been accessed by very few in practice. As a result, a large percentage of pre-independence migrants and their descendants still have no recognised nationality. The same gaps in the law also create risks of statelessness for the descendants of more recent migrants, especially if the parents lack identity documents.

Another significant group at risk of statelessness are people of unknown place of birth and parentage who were found in Côte d’Ivoire as children (foundlings). The 1972 amendments to the nationality code removed the provision that established a presumption of nationality for such children. In 2019, following Côte d’Ivoire’s accession to the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness in 2013, the Ministry of Justice issued a circular that the provisions of the treaty should be applied to issue certificates of nationality to children of unknown parents.

Although a special law adopted in 2013 provided for acquisition of nationality by declaration during a temporary period for certain categories of people (those who would have been able to acquire nationality up to 1972), only 16,189certificates of acquisition of nationality by declaration were issued by 30 November 2020. In total 123,810 applications were received out of an estimated 700,000 to 1,000,000 potentially eligible.

Being stateless in Côte d’Ivoire can result in significant violations of other fundamental rights, which include lack of access to public education, healthcare and other services; inability to access formal employment, especially in the civil service; impeded family reunification; social alienation and psychological challenges and discrimination. Unlike other non-nationals, stateless people have nowhere to be returned to if subjected to deportation proceedings. However, in 2020, Côte d’Ivoire became the first country in Africa to adopt a statelessness determination procedure, fulfilling an aspect of the country’s National Action Plan and in line with a pledge made at the 2019 UNHCR High Level Segment on Statelessness.

THE RIGHT TO NATIONALITY IN COTE D’IVOIRE

In Côte d’Ivoire, nationality is conferred jus sanguinis (by descent). The Ivorian Nationality Code provides that the child of an Ivorian parent acquires nationality whether born inside or outside the country. However, the law distinguishes between children born in or out of wedlock, and additional procedures will be required to establish the parentage of a child born to parents without a registered civil marriage. Moreover, despite the state’s ratification of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness in 2013, the law does not offer a route to nationality for otherwise stateless children born on the territory or for foundlings.

The Nationality Code is also discriminatory on the basis of gender and disability: a woman who has acquired Ivorian nationality cannot confer nationality upon her children unless her spouse has died (Art. 45(1)), and naturalisation is only available to people without mental or physical handicaps (Art.32). The provisions that regulate deprivation of nationality also fail to include a safeguard to prevent a citizen from being rendered stateless. While conferral of nationality to foreign spouses has been without gender discrimination since 2005, a proposal adopted in June 2023 makes the process more difficult, as foreign spouses now require a declaration from the Minister of Justice, available only after 5 years of marriage, before they can acquire Ivorian nationality.

At the October 2019 UNHCR High-Level Segment on Statelessness, Côte d’Ivoire pledged to grant nationality to otherwise stateless children born on the territory, as well as to reform the nationality law to make it more gender-equal. This pledge has yet to be fulfilled.

A new law on civil registration adopted in 2016 provided the possibility for parents without identity documents to register the birth of a child, and in 2018 a law provided a special procedure to re-establish a person’s legal identity. Public servants lack proper training on how to register new-born babies and are often accused of corruption and extortion, while the general public is ill-informed about birth registration procedures. As of 2016, the most recently available data, only 72% of children under the age of five had been registered at birth.

CHILDHOOD STATELESSNESS IN COTE D’IVOIRE

Due to a gap in the country’s nationality law, people found as children in Côte d’Ivoire of unknown parents and place of birth (foundlings) are unable to access nationality. Provision was made for foundlings in the original 1961 nationality law adopted after independence, allowing them to acquire Ivorian nationality by origin based on a presumption that they were born in the country. However, this safeguard was removed when the law was amended in 1972. Other reforms also removed the option under which a person could acquire nationality at majority based on birth in the territory.

The nationality code provides that birth and descent can only be proved as provided by the law on civil registration (Article 9). This means that people must provide their birth certificate and the nationality certificate of a parent in order to acquire proof of their own Ivorian nationality - whether a certificate of nationality or a national identity card. Birth registration is thus a prerequisite for recognition of Ivorian nationality in practice. All births must be registered within three months, and late registrations fall under the jurisdiction of the local courts, which carries additional costs and conditions.

Campaigns for late registration of birth have been launched at different times to resolve risks of statelessness. Late registration of birth is possible through a court procedure to issue a ‘judgement supplétif’ that allows a birth certificate to be issued. This procedure is reliant on the testimony of two witnesses who can speak to the place and circumstances of the birth. Children who were displaced during the conflict of the 2000s, whether within Côte d’Ivoire or across borders, face particular difficulties, especially if they were separated from their parents.

In 2018, a court decision granted nationality to five foundlings, and another judge subsequently followed that ruling and issued nationality certificates to an additional six foundling children. However, granting nationality to foundlings on an ad hoc basis through court decisions does not offer a holistic and appropriate solution to the issue. In 2019, at the UNHCR High-Level Segment on Statelessness, Cote D’Ivoire pledged to introduce laws that would grant nationality to children of unknown or stateless parents who had been born or found on the territory and who would otherwise be stateless. In the same year, the Ministry of Justice issued a circular stating that there should be a presumption, in line with international treaties, that children of unknown parents are Ivorian.

NATIONALITY AND CONFLICT IN COTE D’IVOIRE

Côte d’Ivoire has a long history of receiving migrants from neighbouring countries, both pre and post-independence. After independence, liberal immigration policies and large numbers of migrants contributed to the economic exploitation of agriculture and natural resources under the administration of President Félix Houphouët-Boigny. For a period, non-Ivorians also had the right to vote.

However, Côte d’Ivoire’s immigration policies became less tolerant when economic crises hit the country in the 1990s. After Houphouët-Boigny passed away in 1993, Henri Konan Bedié succeeded him as president. In 1995, a new electoral law restricted the right to vote to citizens and required candidates for high level political office to not only be citizens, but have both an Ivorian father and mother – in a bid to exclude opposition leader Alassane Ouattara, who was asserted to be of mixed ancestry. Bédié also repurposed the concept of “ivoirité” - previously used as a cultural term - to denote ethnic eligibility for Ivorian nationality. Highly flawed elections in 2000 led to an attempted coup and the outbreak of civil war, in which the notion of “ivoirité” and the question of access to national identity documents was a central issue. Peace negotiations and agreements to end the civil war emphasised the question of nationality and voter registration. Fresh elections were not held until 2010, and were also marked by significant conflict over eligibility to vote.

COTE D’IVOIRE’S INTERNATIONAL COMMITMENTS

In 2013, Cote d’Ivoire acceded to both the 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. Cote d’Ivoire is also a state party to the CRC, ICCPR, CEDAW, ICERD, and CRPD, for which it maintains no reservations against the provisions relating to nationality.

For more information on regional standards and intergovernmental commitments in Africa, see the StatelessHub Africa page.

The content on this page was reviewed by Bronwen Manby, expert on nationality and statelessness in Africa.

[last updated October 2023]

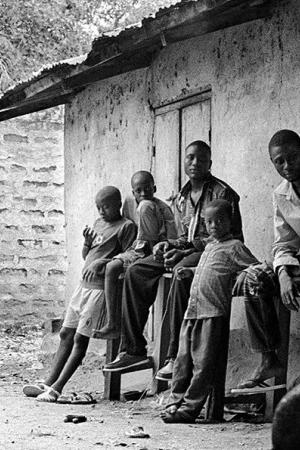

Cover image by Greg Constantine

VOICES & EXPERIENCES

-

Lack of access to Ivorian nationality for foundlings

![Côte d'Ivoire picture]()

Lack of access to Ivorian nationality for foundlings

![Côte d'Ivoire picture]()

“I’m happy to get the documents. It will allow me to go forward in what I want to do … I’m going to fight for others in the same situation as us. I’m going to help them, because I will have the means to do it.”

Christelle

Affected person

Christelle and Francoise look after seven children at Nest orphanage, where they themselves also grew up. They are foundlings as they both lost their mothers in childbirth and were abandoned by their fathers, who refused to recognise them legally. As a result of being without documents, the girls had to endure hardships of childhood statelessness as the Ivorian nationality law requires documentary evidence that at least one parent is Ivorian for the child to be recognised as a national. In a historic court decision following UNHCR and rights groups campaigns, however, the young ladies are said to be “the first foundlings to be granted Ivorian nationality since 1972”. Having been able to succeed in their quest for nationality at the age of 18, they are now helping others in a similar situation.

Voice from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FnEnfUHkU18

-

Marginalised ethnic groups without Ivorian nationality

![cote pic 1]()

-

Gender and disability discrimination in Côte d’Ivoire’s nationality laws

![Cote pic]()

Gender and disability discrimination in Côte d’Ivoire’s nationality laws

![Cote pic]()

Stateless persons in the Ivory Coast are deprived of their most basic human rights. Picture from https://files.institutesi.org/worldsstateless17.pdf .

Latest Resources: Côte d’Ivoire

-

Blog: Cattle Herders Face a Life in Limbo in Côte D’Ivoire

Type of Resource: News/ Media reporting / Blog

Theme: Minorities

Region: Africa

View -

-

Country Examples of Data Collection on Statelessness Statistics

Type of Resource: Legal instruments / Jurisprudence

Theme: Data / Statistics

Region: Africa

View